Two weeks ago I jabbered on about which books I like to read leading up to October 31st.

This week, I’m composing a variation for that theme. What follows are the three

scariest movies I have ever watched, hands down. I’m not talking sudden scares

that make me jump and leave me feeling pissed for the following three seconds.

I’m talking about movies that stay with me long after they’re over and, if I

may be so candid, might necessitate turning on a few more lights when I head

off to sleep.

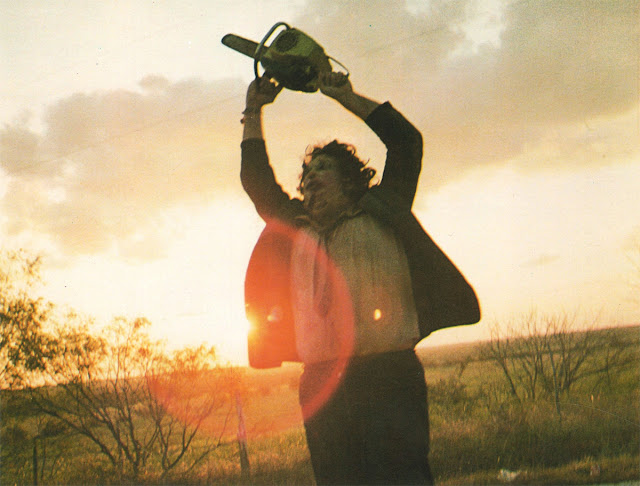

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

While it

undoubtedly inspired much of the slasher genre that dominated the eighties,

Tobe Hooper’s 1974 film has relatively little to do with the likes of the Halloween, Friday the 13th or Nightmare

on Elm Street series, or even the remake and its prequel, which followed in

its wake. While slasher films frequently rely on gore and jump scares, Texas differentiates itself from that

genre (all the better for it, in my opinion), by emphasizing brutal realism and

intensity.

Its plot is

minimal: five college-age kids travel through rural Texas in their van, on

their way to a graveyard. There’s recently been a series of graverobbings in

the area and two of the friends, brother and sister Franklin and Sally

Hardesty, are making sure the bodies of their deceased aren’t among the

missing. In their travels, they earn the ire of a deranged, self-mutilating

hitchhiker, and stumble across an old farmhouse occupied by the skin-wearing

and hammer- and chainsaw-wielding Leatherface.

What The Texas Chain Saw Massacre lacks in

story, it more than makes up for in sheer, unfiltered terror. From

approximately the forty-five minute mark onward, the movie becomes a

no-holds-barred chase, with nary a moment for the viewer to catch their breath.

Daniel Pearl’s cinematography bares greater resemblance to a documentary or art

house film than the careful, Hitchcockian shot selection in John Carpenter’s Halloween. Nearly every facet of the

film, from its grainy look to the chaotic, onomatopoeic score to the admittedly

amateurish acting lend an undeniable sense of realism to the whole affair,

making it all the more difficult to separate oneself from the events on screen

until well after the first few seconds of deafening silence that follow the

movie’s final shot.

Inland Empire

I wrote about

David Lynch’s 2006 magnum opus Inland

Empire a couple years ago, and while that piece was made mostly in jest I

maintain its long-lasting effect on me. While a lot of Lynch’s work has been

called dreamlike, Inland Empire is

truly the first in his filmography—Hell, maybe the first movie ever—to

accurately capture the jumbled, unself-conscious narrative of a dream. Filmed in

digital video, the high frame rate and natural lighting of which give the movie

a strangely intimate feel, it’s a nightmare recorded and screened for our

pleasure—or, more likely, horror.

The film follows

L.A. actor Nikki Grace, played by an extremely underrated Laura Dern, as she

lands a coveted role in a Southern romance co-starring Justin Theroux’s Devon

Berk and directed by veteran filmmaker Kingsley Stewart (Jeremy Irons). Stewart

reluctantly reveals the film is a remake of an aborted Polish movie, scrapped

after both its leads were murdered and the project itself rumoured to be

cursed. As if fulfilling this omen, Nikki gradually becomes unable to differentiate

herself from her character, Susan Blue, and the remaining two thirds of Lynch’s

three hour movie devolve into a whirlwind of settings, characters and events,

held together by the incomprehensible but strangely sensible logic that all

dreams are made of.

It’s difficult

to describe what makes this movie so frightening. It’s oddly realistic, though

completely unlike the realism of The

Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Rather,

the stylistically accurate portrayal of a nightmare hits close to home. It’s an

abstract kind of horror, and requires a lot of endurance on the part of the

viewer, but it’s an experience like none other.

The Blair Witch Project

I missed out on

the Blair Witch craze back during the

film’s release in 1999, then being 10 years old and far, far too afraid of the

horror genre to devote more than a second watching even a non-scary part of

Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez’s low-budget blockbuster. I didn’t watch it

until my first year of university, and even then it was divided into parts on

YouTube, but it dug its fingers into me in a way I never could have predicted. Though

I might be biased, having a love for horror set in the woods—Lars von Trier’s

not nearly as scary but incredibly disturbing Antichrist and Sam Raimi’s The

Evil Dead fall into this category as well.

I really don’t

have to say much about the plot: three film school students venture into the

Maryland woods to film a documentary, students get lost, everything goes to

Hell. While detractors summarize The

Blair Witch Project as a lot of screaming and shaky camera work, credit has

to be given to actors Heather Donohue, Joshua Leonard and Michael C. Williams

(playing “themselves,” as it were). Their performances are completely natural

and believable, akin to the ensemble cast in Alien, and to see their partnership buckle, reaffirm itself and

eventually be decimated is undeniably

involving.

The title doesn’t

really indicate the kind of horror the students in this movie face. I don’t

think anything can describe that

horror; after so many viewings, I’m unable to attach it to any being, physical

or incorporeal. The more I think about it, the more I’m convinced those poor

bastards awaken pure malice, unbound

to any form or body. And that’s what’s so terrifying about the film’s events:

no matter how hard these kids try, it’s all in vain, because you can’t fight or

escape a force as natural and omniscient as gravity. To this day, the final

moments still send a shiver up my spine, and I’ll be damned if I don’t enjoy

the feeling in spite of myself.

No comments:

Post a Comment